Christmas Cookie Inflation Index, 2024 Update

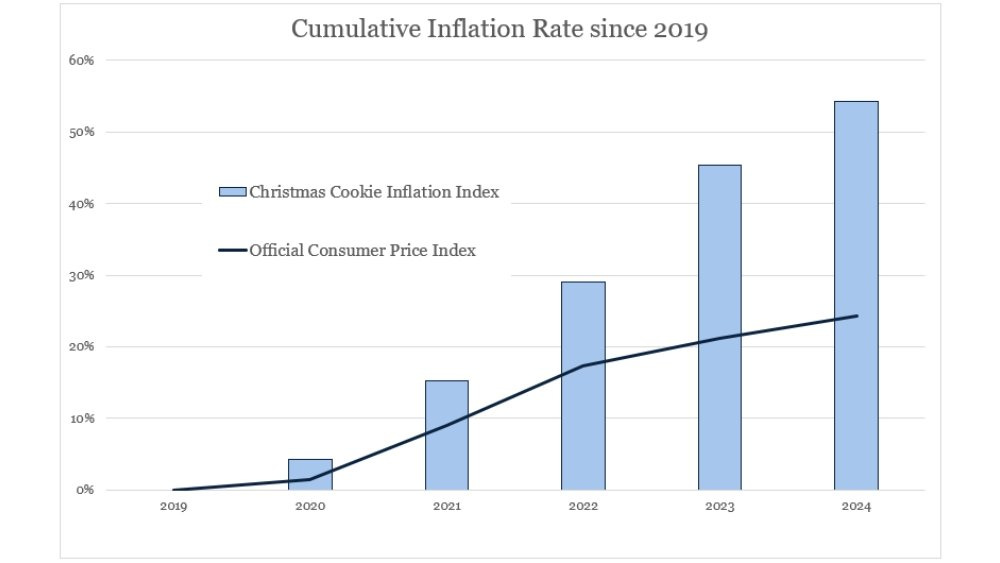

The Christmas Cookie Inflation Index has risen 6.2% in the last year. This is compared to the official inflation rate of 2.6%.

“Inflation has been tamed. Consumers are spending like crazy. Companies have more jobs available than job seekers to fill them. What more could you want, America?”

Indeed! All of the official statistics suggest that things have rarely been this good. That particular quote from a CNN article was part of a series of articles across the media landscape making this same point. In essence, what is wrong with all you rubes?

A narrative divergence like this strongly suggests that something is wrong with the story. Either Americans are ungrateful, spoiled, and out of touch with reality — refusing to believe how good they actually have it — or the official statistics don’t reflect lived reality the way economists, politicians and policymakers want to believe they do. I strongly believe the latter.

Five years ago, I established my own inflation index to track the price of a basket of goods I purchase annually for baking Christmas cookies. These are the same items, in the same quantities, of the same brand, from the same store — literally the same shelf — measured on the same day each year. There are no adjustments or substitutions; just the exact same things tracked over time. I call it the Christmas Cookie Inflation Index.

The Christmas Cookie Inflation Index (CCII) is not a broad measure of inflation. It’s not meant to replace the Consumer Price Index (CPI) or any other official statistic. It is merely a small reality check. The more the simple and straightforward math of the CCII diverges from the reality presented by the nation’s economists and official statisticians, the more it suggests that those official numbers are wrong.

And it definitely diverges. This year, official inflation is up 2.6% while the Christmas Cookie Inflation Index rose by 6.2%. My basket of baking goods has risen by 54% since I started tracking the CCII in 2019. Official inflation is only up 24% during that time. This is the fifth straight year that the reality I have experienced at the store is dramatically out of alignment with official statistics.

For transparency, I’ll note that I am not getting my almond bark at the same store as in prior years. There was a big spike in price this summer (I ran this index in August, just because of my own curiosity). My local grocery store stopped carrying the brand I’m used to using and now only offers the generic store brand. It’s a dollar cheaper ($3.99) than what I show here ($4.99), but it’s also much lower quality. I am getting my preferred almond bark, the kind I always use, for $4.99 at a different store and that price is reflected here. It was $5.99 in August.

I’ve been doing this long enough to have heard most of the counterarguments. The main one is that my CCII index focuses solely on baking goods while CPI is far broader. This is true, but I’ll note that, once again, the official number for food inflation (2.1%) is lower than CPI (2.6%), and that food number is distorted by the price of “Food away from home,” which includes service costs. What kind of world is it where food prices broadly increase by 2.1%, yet baking goods — which are also food — rise by 6.2%? That doesn't make sense. It's not like you go to a grocery store and prices are down everywhere except for flour, sugar and spices.

With six years of data, the modest variances year after year start to really add up. My Christmas baking costs far more than it used to. In real terms, anyone doing similar baking is falling way behind, even if their wages/salary keep up with the official inflation rate.

Inflation is in the news this year, of course, because it was a major issue in the election. That prompts me, before going any further, to issue my standard disclaimer: I don’t think inflation is caused by Democratic policies, just like I don’t think inflation is caused by Republican policies. It is a phenomenon of our system, the result of economists fighting the last battle (the Great Depression) in a way that generally works for the empowered, paired with the right marketing (generous statistical outcomes) to soothe their consciences.

In the 1990s, when Newt Gingrich led a bipartisan effort to “fix” how the CPI was calculated, it was done with the explicit understanding that a lower inflation rate meant social security (which adjusts each year to keep up with the official inflation rate) would grow more slowly and the burden of making interest payments on federal debt would be lessened. This is a great way (on paper) to balance a budget without having to raise revenue or cut programs. You don’t have to believe in ill intentions to recognize that everyone who wants a powerful state (that is, everyone empowered by it) has rational reasons to believe in an approach that consistently produces a low inflation story. Stated another way, nobody in a position to influence the way official inflation statistics are calculated has an incentive to overstate it, but they have lots of incentive to understate it.

There are two parts of the inflation story that interest me this year. The first has to do with the 2% inflation target, a concept that had been debated for years but was made explicit in 2012. The underlying idea is that 2% inflation is the right balance between an economy that is growing robustly (which tends to drive inflation upward) and unemployment (which tends to rise when the economy slows). In other words, an economy with less than 2% inflation has room to be stimulative in pursuit of more employment.

I’m skeptical of this concept, but I will acknowledge that I am less studied in it than the people who debated it for decades. I take our nation’s economists (Yellen, Powell, Bernanke, etc.) at their word that they believe in the 2% target. I also understand how all humans are challenged by motivated reasoning and struggle to reconcile their beliefs with their actions. It is not hard to discern how our top economists think about inflation when it comes to the 2% target.

In July 2019, the CPI was slightly below target at 1.8%. Over the prior 12 months, it had varied between 1.5% and 2.2%, with four of the prior five months being 1.8% or higher. This is about as close to target inflation as it is possible to get. If you're targeting 2%, it might be a good time to keep a steady hand on the rudder. Yet, what was our interest rate policy?

Yep, we cut rates. The disposition was to juice things, to get the economy growing faster. The Federal Reserve had been slowly reducing its balance sheet in the first nine months of 2019, but that also reversed dramatically in September, closing the year with near-record levels of monetary expansion. Note that this was prior to the pandemic and more than a decade after the 2008 financial crisis. Instead of being content at very near 2% inflation and letting things run their course, our top economists were trying to wring every last bit of growth out of the economy.

Contrast that disposition with what we experienced in 2024. Just as in 2019, we have historically low unemployment. And, just like in 2019, we have a booming stock market. Yet, inflation this past July was above target at 2.9%. It was further above target — and had trended above target for longer — than inflation was below target in 2019. If there is a commitment to the 2% target, there should be some kind of symmetrical response. Yet, here is where we were in July of this year.

Even though inflation has held steady well above the target rate of 2%, the Federal Reserve has cut interest rates twice this year, first by half a percentage point and then by another quarter percent last month. Again, the disposition here is to juice things, to get the economy growing faster, just like in 2019, despite being above target on inflation.

I am going to make a statement that might feel controversial to some, but at this point should be self-evident: Our nation’s top economic officials are quite sensitive to inflation being too low, but they are not sensitive to an inflation level that — by their own measure — is too high. When inflation is too low, they will do radical things to increase it. When inflation is too high, they are willing to risk it going higher just to squeeze out a little more growth. If they are going to err on inflation, they would prefer to err with too much than with too little.

This is a gentler way of saying what I’ve believed for years: Our nation’s leaders prefer persistently high levels of real inflation, and this preference not only invites the downward distortion of official inflation calculations but also tolerates policies that give us occasional bursts of very high inflation. The official gaslighting on inflation is one reason I started the CCII; I just needed something stable to validate to myself that we all live on a financial treadmill that continues to speed up.

I’ll make one more observation before moving on: High inflation might be popular among economists and our nation’s policymakers, it might be cheered by investors and those who magnify their wealth through leverage, and it might be tolerated by the highly educated who were taught pro-inflationary theories in a graduate economics seminar, but average people hate it. They loathe it. To them, inflation feels like water eroding a shoreline, a relentless sense that, with each passing day, they are losing more and more ground through no fault of their own.

Go back to the beginning of this column. “What more could you want, America?” Americans don’t want lower levels of inflation. They don’t want the shore to erode more slowly. What they want is no inflation at all. Unfortunately, that puts them at odds with our nation’s leaders.

The real question now — and this is the second thing that is fascinating to me about the inflation story this year — is how long this can continue without a phase shift. How long can we have the officially reported inflation rate remain above the 2012 elevated target of 2%, with the actual rate experienced by everyday people meaningfully above that? At what point do policymakers lose control of this story?

Let’s be clear: I thought they lost control 15 years ago. I was wrong. I’ve been shocked (and a bit appalled) each day since the 2008 meltdown. I’m not going to make any predictions about what comes next, mostly because I have demonstrated to myself that I continually underestimate both our ability to prop this system up and our desire to believe that doing so is okay. Even so, it feels like we’re on borrowed time.

What does it mean for policymakers to lose control? It's simple: It would manifest in the Federal Reserve's inability to control the long-term interest rate. There are signs that this is already starting to happen.

In September, the Federal Reserve lowered the overnight borrowing rate by half a percentage point — 50 basis points, as they say in the business. If the Fed were exerting control over the bond market, the expectation is that longer-term rates would fall by around half a basis point. That is what initially happened with 30-year mortgages, but then things reversed.

The “why” in the above article points to 10-year notes, which are also rising, but the article doesn’t really explain why. Obviously, rates are rising because there are not enough buyers for 10-year bonds. When there aren’t enough buyers at low rates, rates rise until there are enough buyers to fill the supply of bonds on sale. So, why aren’t there enough buyers for 10-year bonds?

There are lots of explanations, from rising federal deficits crowding out the private bond market to just the fickle nature of markets. One possible explanation, one I personally find likely, is that bond investors (reasonably) anticipate a future of higher inflation, and thus a future of higher interest rates, and they don’t want to get stuck for the next decade with a low-interest note.

Higher inflation would theoretically drive rates higher. Higher rates on the federal debt will explode the federal budget deficit. Since the federal government is already paying more for interest annually than it does for defense, higher interest rates threaten to overwhelm the federal budget and severely limit government spending. The Federal Reserve can alleviate this fiscal constraint by printing more money and using that cash to purchase federal government bonds. This will keep interest rates down — with the Federal Reserve buying bonds, there's no need to raise rates to attract other buyers — but an influx of newly printed money will almost certainly accelerate inflation to acutely painful levels.

So, losing control means the Federal Reserve would have to decide whether to protect federal government spending by embracing high levels of inflation or deal with inflation regardless of the consequences to federal spending and the broader economy. If faced with this decision, I am almost certain they will choose inflation, the path chosen by nearly every overextended government facing similar circumstances throughout human history.

Apparently, there is a segment of investors that thinks this scenario has a high enough likelihood of occurring to put real money behind it. For a variety of reasons, I’m not into cryptocurrencies, but I do track the price of precious metals. Gold and silver won’t make you rich, but they are a reasonably sound hedge against high levels of inflation. This has been a robust year for both metals. Each is up around 28% so far in 2024.

The thing about inflation is that, once people start to believe in it, their actions can make it happen. If an investor believes inflation is going to be higher in the future, they will hold back from longer-term notes, driving the price of those notes higher and creating inflation. If a worker in a tight labor market believes they live in an inflationary environment, they will demand higher wages or seek to switch jobs for more pay, thus raising employer costs and, subsequently, raising prices.

So, the Federal Reserve and federal finance officials can tell us that inflation is under control and not likely to be a problem. News organizations like CNN, The New York Times and The Washington Post can tell us that inflation is not that bad and that we should all stop being so pessimistic.

That may work for a while, but when people go to the grocery store to buy sugar and spice so they can bake the Christmas cookies they have enjoyed for their entire lives, the ones that their grandmothers used to make, the ones that are a sacred family tradition, and the ingredients cost 54% more than they did five years ago, they are not going to believe the official numbers that inflation is only up 24% during that time.

They are not going to feel grateful that things are only 6.2% more expensive now than they were last year. They are not going to support the people who are telling them it’s not that bad, that prices have only gone up 2.6% this year, that their wages are (on average) keeping up. They will not believe something that they know isn't true.

And when you ask them what they think is going to happen in the future, they are going to report — in record numbers — that they think inflation is going to be much higher in the future.

And that is how you lose control.

You can read past reporting on the Christmas Cookie Inflation Index for 2023, 2022, 2021 and 2020.

Chuck, this is always interesting. I'm no economist either, but my feeling is the same. We live a modest rural lifestyle and dutifully budget in our household -- and our lifestyle has not changed for many years (so basically our basket of goods has not seen any big changes). From 2014 to 2019 our expenses stayed flat. Our 2023 expenses were up 52% from 2019. Is our income up 52%? Not even close. Where the economists get these inflation figures from is puzzling. I was tired of being told that the economy is doing well. The only ones it seems to be doing well for are upper income people. Everyone I know feels squeezed.

There's also the Christmas Cookie Infiltration Index. This is the rate at which your stash of Christmas cookies is infiltrated each year, pilfered by passers by, children, pets and even the baker himself. It's expressed as the percent of yield that doesn't reach its intended consumers.